The wobbegong shark: the cuddly master of camouflage in the Papuan seas.

- The Introvert Traveler

- 23 lug 2025

- Tempo di lettura: 5 min

One of the most extraordinary journeys I’ve ever taken in my life was to Raja Ampat, in West Papua, where I spent a full week diving in what is, without a doubt, the most astonishing underwater environment I have ever seen.The seafloor of Raja Ampat is an ecological marvel, teeming with thousands of lifeforms—some of the most bizarre and unexpected I’ve ever encountered. It feels like a primordial biological laboratory, where Mother Nature dared the unthinkable and gave life to the most unpredictable prototypes and experimental blueprints.

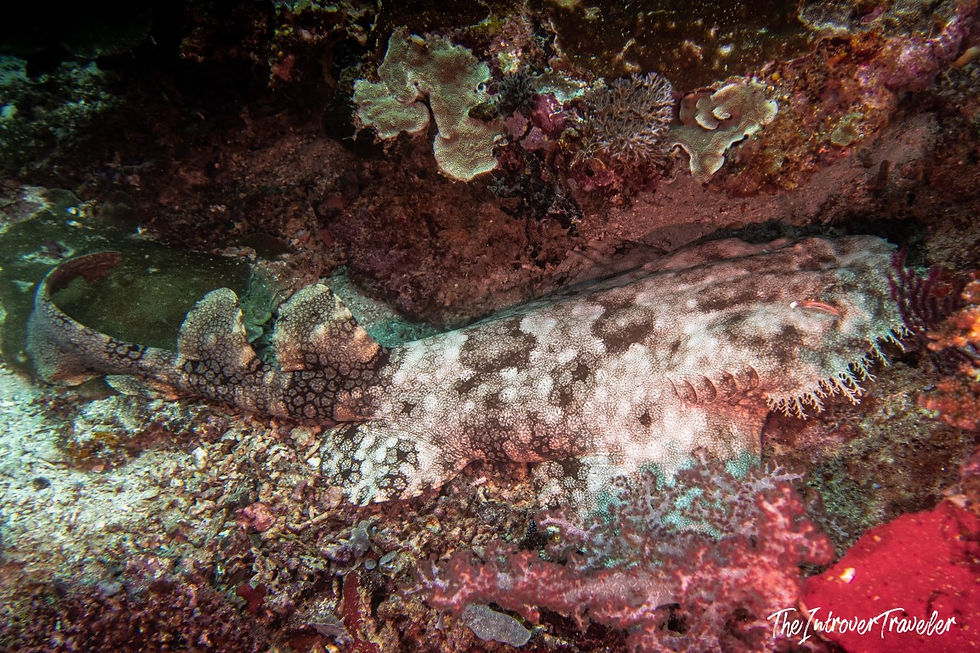

Among these incredible, improbable, and downright surreal creatures is the wobbegong shark—a species that can be spotted in Raja Ampat and in very few other places on Earth. Sightings are so frequent there that, by the end of my stay, I had nearly started to take them for granted, not fully appreciating how lucky I was to witness such a remarkable animal with my own eyes.

So here it is: a collection of facts and fascinating details about this natural wonder.

Taxonomy and Classification

The term wobbegong refers to a group of sharks belonging to the family Orectolobidae, in the order Orectolobiformes—the same order that includes the whale shark. The Orectolobidae family includes around 12 species across three main genera: Orectolobus, Eucrossorhinus, and Sutorectus.Among the most well-known species are Orectolobus maculatus (spotted wobbegong), Orectolobus ornatus (ornate wobbegong), and Orectolobus halei (banded or giant wobbegong).The name wobbegong likely comes from an Aboriginal Australian term meaning “shaggy beard”—a clear reference to the distinctive head morphology of these sharks.

Distribution and Habitat

Wobbegongs are native to the western Indo-Pacific, with their highest concentrations found off the coasts of Australia, Papua New Guinea, and Indonesia. Some species, like O. japonicus, extend as far north as Japan.They prefer rocky reefs, coral gardens, and seagrass meadows, typically at depths ranging from 0 to 100 meters, though sightings have been recorded down to 200 meters.Wobbegongs favor complex underwater structures, which enhance their camouflage and offer protection from both predators and strong currents.

Morphological Features

Wobbegongs are distinguished by their flattened bodies, broad heads, and depressed profiles—classic adaptations of bottom-dwelling (benthic) sharks. Depending on the species, their length ranges from 1 to 3 meters (O. halei being the largest).Their color patterns are marvels of natural design: intricate mosaics of reticulated lines, blotches, and rings that perfectly imitate coral and rocky substrates.They have small eyes placed dorsally, and their pectoral and pelvic fins are wide and rounded.Their teeth are small and needle-like, ideal for gripping slippery prey such as bony fish and cephalopods.

Dermal Fringes: An Evolutionary Masterpiece

One of the most fascinating features of the wobbegong is the presence of dermal fringes surrounding the mouth area and sometimes extending along the edges of the head. These filamentous, highly branched appendages serve multiple purposes:

Camouflage: They help break up the shark’s outline, making it nearly invisible among rocks and corals.

Sensory function: These fringes house sensory papillae that enhance the shark’s ability to detect vibrations and water movements.

Luring prey: Their worm- or algae-like appearance may entice small fish and invertebrates to approach, mistaking them for edible organisms—setting them up for the shark’s lightning-fast ambush.

These fringes (clearly visible in this close-up I took in Raja Ampat, just a few centimeters from the mouth of a wobbegong who—despite my tactless intrusion—tolerated my presence with admirable patience) represent a rare case of functional convergence between cartilaginous fishes and certain benthic bony fishes, such as some species of scorpionfish.But this remarkable adaptation is not shared only with benthic fish—it also appears in species that live in completely different environments from that of the wobbegong.And that, to me, is the most fascinating aspect.

Indeed, dermal fringes that are almost identical in form can be found in fishes of the family Lophiidae—typically the anglerfish. That in itself is a compelling fact: Lophiids are evolutionarily quite distant from elasmobranchs, and yet… one might say, superficially, “They’re all predatory fishes inhabiting similar benthic zones—it’s not that surprising they developed similar evolutionary strategies.”

But here’s what truly astonishes me: apparently identical structures have also evolved on land, in species that do not share habitat, ecological niche, or even functional purpose.I’m referring in particular to the Uroplatus sikorae, a gecko endemic to Madagascar, who—utterly indifferent to the laws of probability or any concern for plausibility—displays along its body dermal fringes that are nearly indistinguishable from those of the wobbegong or the anglerfish.

(The following photos of the gecko are courtesy of Lindsie Nicole, published at www.monaconatureencyclopedia.com. I do not know the authorship of the two Uroplatus images.)

So what? Nothing in particular—except that nature never ceases to amaze me.

Disclaimer: I'm not an expert in evolutionary biology or marine science. It’s entirely possible that the dermal fringes of the gecko are something completely different from those of the wobbegong. Perhaps this feature is present in many other species as well. I’m merely sharing what I find astonishing, along with the current state of my knowledge and my enduring sense of wonder toward the natural world.

Ecology and Behavior of the Wobbegong Shark

The wobbegong is a classic ambush predator: it spends most of its time lying motionless on the seabed, waiting for unsuspecting prey to come too close. It is mostly nocturnal and displays sedentary behavior, though it may move across moderate distances in search of better hunting grounds. Its diet consists mainly of bony fish, crustaceans, and cephalopods. Reproduction is ovoviviparous, with litters reaching up to 20 fully formed pups at birth.

In my extremely limited experience, the wobbegong is an exceedingly docile animal. On several occasions, I approached within mere centimeters to take photographs, and the wobbegong didn’t show the slightest irritation.Looking back, this behavior of mine (not particularly prudent, in hindsight) was likely influenced by the comfort and familiarity local dive guides showed when interacting with these animals.

Later, through my readings, I learned that wobbegong bites on divers are not unheard of.While their bite is nothing like that of other, more infamous sharks, it is certainly unpleasant, especially because the wobbegong has a rather tenacious grip—once it bites, it tends not to let go, which can cause serious injuries such as broken fingers or forearms. So: a bit more caution than I showed would definitely be advisable...

Why the Wobbegong Is Incredibly Cool

The wobbegong shark is not only an evolutionary marvel—it’s also a masterclass in style and strategy.Imagine a predator that doesn’t waste energy chasing its prey, but instead turns itself into part of the seafloor—a living trap.The wobbegong doesn’t need jet-like speed or massive jaws. Its weapon is invisibility.

And those fringes?They’re the height of biological sophistication: aesthetic, functional, and deadly (if you're small and careless enough to come too close).

In short, the wobbegong reminds us that nature doesn’t only reward brute strength or speed, but also ingenuity and perfect adaptation.And beyond that: it’s a peaceful animal toward humans (as long as you respect its space) and a symbol of marine biodiversity in the southeastern Indian Ocean—worthy of admiration and reverence.

Conclusion

The wobbegong is a perfect example of how evolution can give rise to extraordinary lifeforms, superbly adapted to their environment.With its camouflage, dermal fringes, and specialized predatory habits, it offers a fascinating case study for marine biology enthusiasts—and a humbling reminder of how much more there is to discover beneath the surface.

Below, to round out the visual content, are some videos I shot in Papua.Yes, I know—they’re pretty awful. But with a compact camera at 30 meters deep, in low-light conditions, that was the best I could manage.